Today’s review is written by Tova.

Today’s review is written by Tova.

“How well do you know the people who raised you?”

Journalist Michele Norris presents this question to the reader in the epilogue of her book The Grace of Silence: A Memoir. In her work—as much an investigation of the painful historical realities of race in America as a memoir—Norris reaches deep into the depths of her own family history and illuminates this country’s racial past along the way.

Originally intent on writing a book about the “hidden conversation” on race taking place in a supposedly “postracial” America in the wake of Barack Obama’s election to the Presidency, Norris changed course when she discovered that the conversation on race within her own African American family had not been honest. She discovered two family secrets: her maternal Grandmother Ione had been a traveling “Aunt Jemima” in the Midwest, and her father Belvin Norris had been shot in the leg by a white police officer in Birmingham shortly after his discharge from the Navy at the conclusion of World War II. Uncovering these secrets shakes Norris’s sense of her identity: “These revelations suggest to me that in certain ways I’ve never had a full understanding of my parents or of the formation of my own racial identity.” The majority of the book is devoted to discovering who her parents really are and, by extension, who she herself is. Why did her parents intentionally keep these secrets from her?

Most jarring about these revelations, for Norris, is that they are incongruous with her conception of her parents. Norris writes of her father: “how could a man who always observed stop signs, a man who always filed his taxes early and preached that jaywalking proved a weakness of character have been involved in an altercation with Alabama policemen? . . . Why would he impart life lessons to us about looking the other way, turning the other cheek, respecting those who lived across the color line in spite of insults hurled our way, when he himself had not?”

What Norris discovers along the way in her journey to answer these questions is surprising, revealing, uncomfortable, and thought-provoking for both her and the reader. I found myself getting emotional at times while reading the book. My eyes watered when Norris described brutal attacks on African American World War II veterans and their families. I found myself groaning inside when a relative of one of the officers involved in the shooting of Belvin Norris remarked to the author, “I don’t have anything against [African Americans], only the ones who are snooty or trying to prove themselves,” and then referenced President Obama as an example. But that’s what this book does. It hits you in the gut. I suspect that no matter your racial or cultural background, this book will “ping” your emotions in many different ways.

While this is not an “easy” book—as it challenges you emotionally and makes you think about certain ugly truths that some would rather not acknowledge—it has its moments of levity. You will smile wryly at the ingenious ways in which Norris’s mother foils the attempts of her neighbors to sell their houses and flee the neighborhood after the Norris family integrates it. You will also be touched by the loving relationship Norris has with her father. In a sense, this book is an extended love letter to her father. Even while championing an open dialogue about race, Michele Norris appreciates that her father early-on made the decision to remain silent as part of a strategy to ensure that his children would not be hindered by bitterness and acrimony in their struggle to achieve.

When I read the premise of the book, I was immediately drawn to it. I, too, am African American. I am familiar with the silences surrounding family secrets dealing with race. As a result, I found myself constantly comparing the strategies adopted by Norris’s family in dealing with racism to those of my own family. Norris’s mother and father concerned themselves with trying to be “model minorities.” My mother, a single parent and Black Power activist, made a different choice and took a different route in raising her children. My mother, just like her father, taught us that we should be angry about racism. This anger provides the fuel for my activism. Norris’s book exposes a particular truth, that we, as African Americans, have adopted multiple and varying strategies for navigating within a racially hostile world.

In the end, Norris suggests that we can come to a fuller understanding of who we are individually and as a nation by being more open about race. One thing Norris discovers is that white families also have their racial secrets and silences. Most of the families of the police officers involved in her father’s shooting either had no clue of their family member’s involvement in the shooting, or the family members did not want to talk about the incident.

How many of our families, regardless of our racial or cultural backgrounds, harbor secrets relative to race? What do these silences tell us about the state of race in America? Norris’s work, The Grace of Silence: A Memoir, is a call to all of us to sit down and ask questions. If we are to truly move racially forward as a nation, we must hear our family stories. We must question our elders, and we must listen to not just what is said, but what is not said.

Check the WRL catalog for The Grace of Silence.

It’s also available as a CD audiobook, read by the author.

Read Full Post »

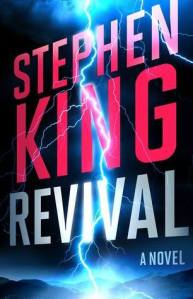

We finish our week of superb blog posts from the Outreach Services division with Tova’s take on the latest by the prolific and talented Stephen King:

We finish our week of superb blog posts from the Outreach Services division with Tova’s take on the latest by the prolific and talented Stephen King: Today’s post is written by Tova from Circulation Services.

Today’s post is written by Tova from Circulation Services.